Together Ken and Morris have created nearly a hundred projects

Collaborators

METADRAMATIC DESIGN IN THE STAGE WORK OF MORRIS PANYCH AND KEN MACDONALD

Panych and MacDonald have produced a varied body of work, appearing together as writers and actors, and working individually (but often on the same production) as director, production designer and musical director. At times, they have shared the creative process with other writers and directors; at other times, they have created the entire production themselves. These artistic activities are usually seen as distinct, but, in this continuing partnership, mutual approaches consistently surface, even when the team is working with others. Because they work on different aspects of the design and production of their shows but with a common vision, their collaborations present a rich source for the study of the necessary interplay among production specialists. But, more important, their work also demonstrates the intricate relationship between the illusion created and the act of creation. Their work shows a conscious manipulation of dramatic text and stage effect to produce an array 'of pragmatic utterances,' to create what Elam calls a 'dramatological approach' rather than one 'dedicated to sjuzet and fabula alone' (144).

Through their work, from their early collaborative writing and acting in Last Call: A Post Nuclear Cabaret to their involvement in the Tamahnous Haunted House Hamlet, to their popular Arts Club (summer 1989) production of 7 Stories (which opened at Tarragon Theatre in February 1991) to their partnership in the design, textual emendation, and direction of the Arts Club's 1989 production of Shakespeare's Comedy of Errors, to their adaptation of The Beggar's Opera at Studio 58, Panych and MacDonald have consistently played with the barriers of illusion and have superimposed upon the narratives they present the palpable presence of themselves as agents of creation and of the stage as a metadramatic process.

Ken MacDonald

Morris Panych

From the Theatrebooks website

Playwright Morris Panych and his partner, designer Ken MacDonald, have been a vibrant part of the Canadian theatre community for twenty years. Their new show, Girl In The Goldfish Bowl, opens this week at Tarragon Theatre. The show debuted at Granville Island Stage, under the direction of Patrick McDonald, this spring.

TheatreBooks sat down with Morris and Ken to talk about the show, new challenges, and the luxury of doing two different productions of the same play.

TheatreBooks: Tell me the story.

Morris Panych: It's the story of a girl who brings a man home who she finds on the beach.

Ken MacDonald: He's a mysterious stranger.

MP: Her parents are in the midst of breaking up, her mother is going to leave the house, and she's trying to save her family. And she thinks this man is her reincarnated goldfish.

KM: The goldfish has just died, and this man washes up on the shore. She thinks he looks a little bit like her goldfish did, if he was a human. He's got some kind of similar markings on his neck. She places great importance on her goldfish.

MP: It's as if somehow the goldfish had kept the world in order and when it died, everything fell apart -- that's what she thinks. When this man appears, things start to look like they're coming together again.

That's basically the set up of the story.

TB: What about Girl In The Goldfish Bowl represents material or themes that you -- both of you -- haven't looked at or explored before?

MP: It wasn't new territory for Ken. The set is somewhat surrealistic, but it's not something he hasn't done before. But in the truest sense it's a realistic set . That's something Ken doesn't often do. He usually does interpretive kinds of sets -- there's no huge perspective in this set.

KM: We just kind of go from one side of the set to the other -- we blend from the cannery docks, and the docks start to meld into the house. In the centre it's absolutely realistic, and as it spreads towards the outer edges it turns, so it's a fusion of the inside and outside at the same time.

I never do strictly realistic sets. Absolutely realistic sets are sort of better for film. In theatre we're more conscious that we're watching a stage piece, and it's bigger for life. You can see the lights.

MP: It was new territory for me in terms of the first production in Vancouver. I didn't direct, and I have always directed the first production of my plays. I was just being a writer. That was interesting and instructive.

The theme is new territory. I've never written a play about a child before, or where one of the main characters was a child. It's also less absurd than some of my other work. It's more in the realm of -- not naturalism, but realism.

TB: Did you find any insights on the part of the other director surprising, or did you find the lack of control frustrating?

MP: I chose for it not to be frustrating. I chose to allow myself to let him direct it. It was a conscious choice. I didn't want to interfere. I wanted to see what he would make of my show. .... Because I chose that path, whenever I felt frustrated, I reminded myself that it had been my decision.

There were a lot of surprises, and almost all of them were good surprises. I was surprised by how much -- actually, how much more weirdly seriously he took my text than I did -- almost at face value.

I didn't cast the show, but he wanted my input. The director (Patrick McDonald), of course, however, makes the final decision. So it was like I had input, but I didn't have input. I would have preferred not to have any input at all. It would have crossed less boundaries.

But the way Patrick directs is pretty organic anyway, so we were working together, and working with Ken.

TB: Why did you make the choice not to direct?

MP: I wanted to be a writer. When I'm a director, I have to focus more on the actors and not on my script.

KM: This way he could watch a rehearsal and go away and change some things and rewrite a passage, and care less about tech problems. He also knew that he was going to direct the show himself at Tarragon, so he'd get a shot at it too.

TB: Has your set design changed for this production?

KM: Not very much. The theatre in Vancouver was a quite a bit larger -- it had a lot more height, and a bit more width. But otherwise I went for a very similar look. There wasn't really any point in changing for change's sake.

I have done that -- I did a show here called '2000' for Joan Macleod, which I had done before in Vancouver with the same director. There is occasionally more than one idea I want to try, but in this case we quite liked the original design, and it fit. So I kept it.

TB: Were there any cast members that crossed over from the other production?

MP: I didn't want to come to Toronto and cast a bunch of Vancouver actors. There's a huge, huge body of talent here. And also I wanted a new show -- I wanted my own show. I couldn't have done that with the same cast. It wouldn't have worked out.

TB: Were there moments of inspiration from the Vancouver show that carried over into this one?

MP: There was a lot of staging that I just stole, because it was easier. I didn't have to invent everything from scratch. If we got stuck, I could say "Let's try this," though I very quickly realized that if they did do (the same thing) they would have to be in the same frame of mind as the actors in Vancouver. So we sort of worked our own path through it, but it was easier.

KM: The costume director who worked with us before said "Just steal whatever you want." And I did. It's quite different in the long run, but I didn't have to completely invent something. I had something to fall back on. Normally, however, I much prefer to invent. It's no fun if you just go look up what someone else did.

TB: The Overcoat [a Panych hit at CanStage two years ago] was turned into a short. Do you think that this play would translate well to film?

KM: It's filmic enough in its atmosphere and location, and it has a narrative kind of feeling that works quite well in film sometimes. The little girl could tell the story.

MP: But it's easy enough to say "It would make a good film," but you have to find someone with a couple million dollars. If someone comes to me with 2 million dollars and says "I want to make this into a film," then yeah, we'll do it.

KM: Maybe someone will read this on the website and want to do it.

Kim Blackwell interview; the Overcoat was made into a film two years later

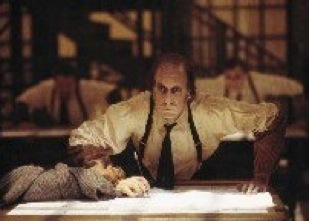

Peter Anderson hunkers down to work in our film version of The Overcoat produced by CBC and Principia Films. It was nominated for 7 Geminis.

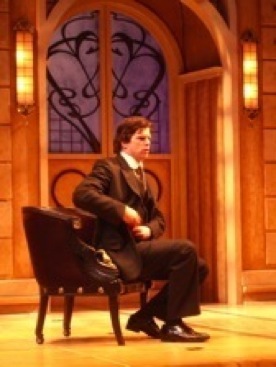

Take Me Out, Canadian Stage

The Dishwashers, Tarragon Theatre

Waiting for Godot, Arts Club

Peter Anderson, Colin Heath, The Overcoat

Randy Hughson, Eric Peterson, The Dishwashers

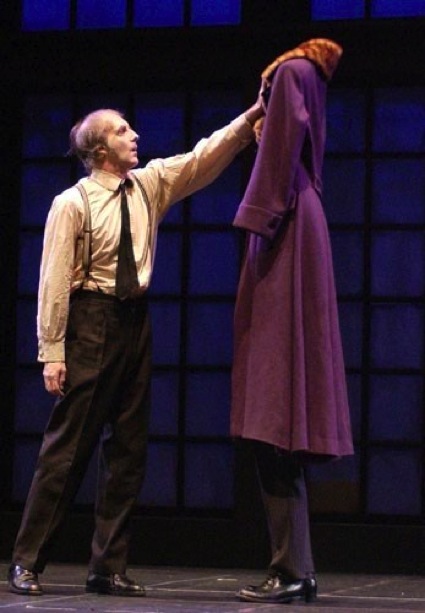

Mike Shara, below Jennifer Lines, David Marr

The Amorous Adventures of Anatol

Morris Panych, Jennifer Phipps, Vigil

Patrick Galligan, Charlotte Gowdy, Hotel Peccadillo

Randy Hughson, Earshot

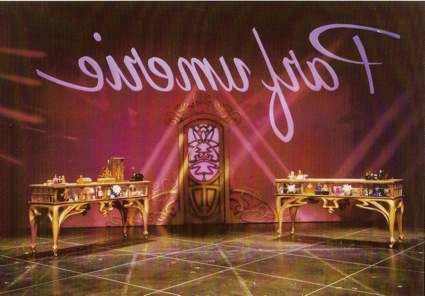

Set for Arts Club production of She Loves Me.